Satellite broadcasts from Tierra del Fuego

I worked in London in satellite events management and audio - this is an account of one journey and several broadcasts in the remote wonderland of deepest South America

Satellite broadcasts from South America - a magical place

This is an edited excerpt from my book ‘A Sack of Cats - journeys into Nothingness’ due to be released at some stage in the future. This excerpt is © 2023 Brent Smith, all rights reserved.

Leaving London for Buenos Aires

Saturday 24th September 1994 - Heathrow to Buenos Aires.

I flew out of Heathrow at 10.30pm, 211 Lbs (96 kgs) over the weight allowance with seven flight cases of equipment and two backpacks. I’m part of the satellite and production team sent out to six remote locations around the world, from France Telecom's London uplink base, working on the worldwide launch of a new SUV.

The Independent on Sunday, 2 October 1994, in a major piece entitled “The Selling of a Supermodel”, reported that the all-new vehicle was about to hit the road 24 years after the first, and it took six years and £300m to develop. The journalist, David Bowen, traced the journey from an idea, to the marketing drive that set up a satellite business television network, and sent VIPs all around the world for the SUV launch event.

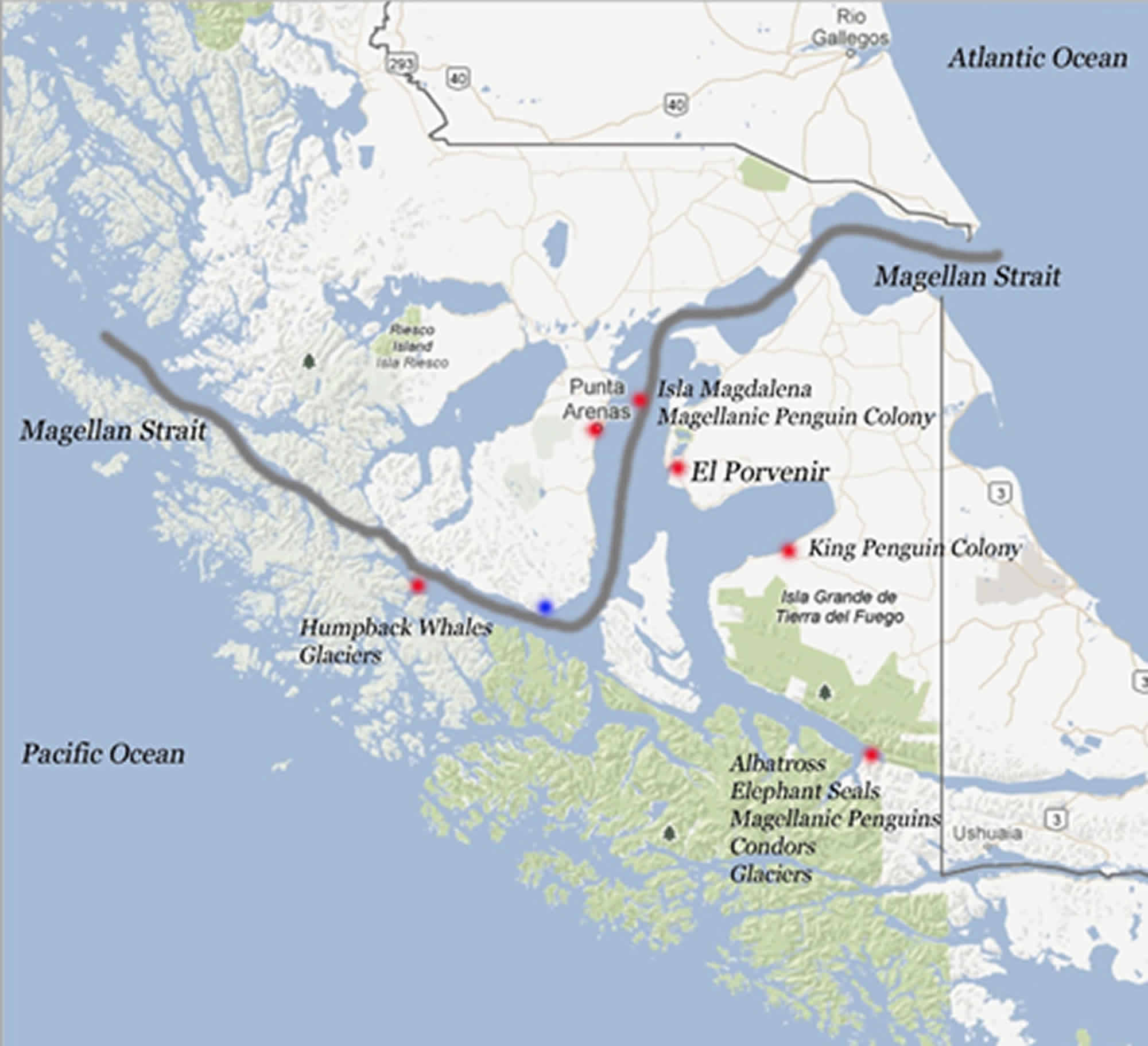

The locations are Cornwell Manor in Oxfordshire; near Chobe River in Botswana; the foothills of Mount Fuji in Japan; Vermont, USA; and Tierra del Fuego in Patagonia. The plan is to broadcast via satellite from these locations to dealerships throughout Europe and to other interested parties, to promote the new SUV.

I’m managing the technical broadcasts and uplinks for South America, and operating the audio that will come in from the London studio, with local radio earpieces for the VIPs, most of whom are on the plane with me to Buenos Aires.

Our company personnel helped with the cases at Heathrow, and I met the VIPs - Robin Knox-Johnston (now Sir), a great personality, and the first yachtsman to sail single-handedly around the world in 1968-69 - accompanied by his lovely wife, Suzanne (1939 - 2003); the British astronaut, Helen Sharman CMG, OBE, HonFRSC; the Swedish glaciologist, Monica Kristensen (Wikipedia: Monica Kristensen Solås); and John Hall, the chief engineer and designer of the SUV. Natalie Goodall (1935-2015), the US born, eminent conservationist, will meet us in Tierra del Fuego, as she then lived locally. (Wikipedia: Rae Natalie Prosser de Goodall).

On the flight also are our broadcast director, Jon Lane, cameraman, Robert Blackmore, and broadcast soundman, Nic Jones. I don't recall meeting Jon at the airport, though we had attended meetings, prior.

When we arrive in Buenos Aires, the plan is to meet the crew of a national satellite engineering company, Keytech, who will be my companions, travelling on a time schedule almost completely different to the main party, including the production crew. We will engage with them at points along the way, but their journey will be very different to ours.

The main party will be driving three SUVs with another three for support personnel, and will join us at each of three transmission sites to broadcast their experiences via uplink, and then depart while we pack up to drive to the next uplink site, to meet them there again.

Onwards to Río Gallegos

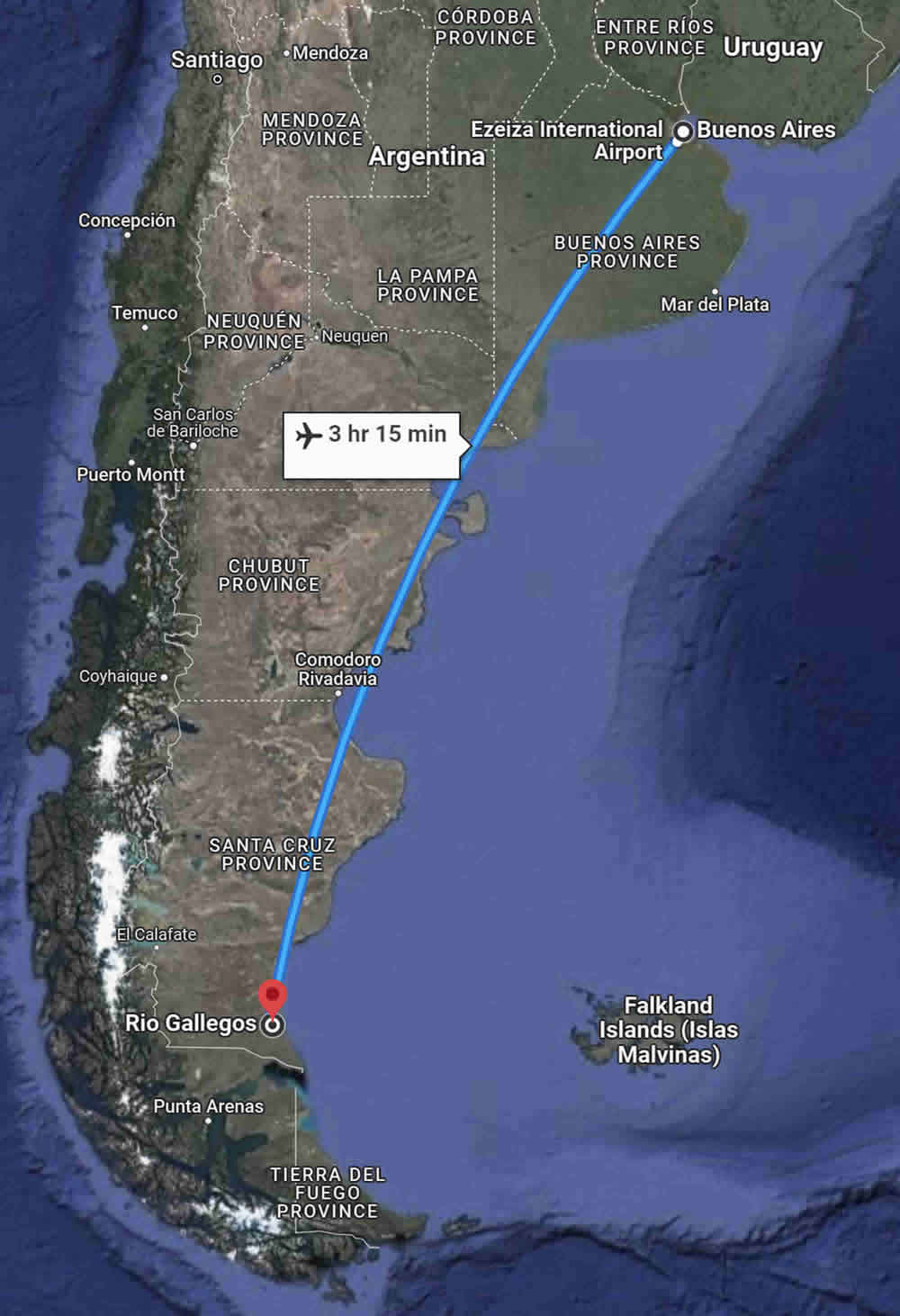

The flight to Buenos Aires takes 16 sleepless hours and I meet Hugo - the Keytech Head of Technical, and local 'fixers' to help us through customs. We say goodbye to the main party and help the fixers transfer us to the domestic airport one hour away, for the flight to Río Gallegos. We pass the Río de la Plata, which may be considered a river, an estuary, a gulf, or a sea (depending on the geographer). It's so expansive in some places that the other bank isn't visible - up to 87 miles (140 kms) wide [1].

The three-hour flight takes Hugo and I, with much increased equipment, down South to Río Gallegos. He teaches me how to say Gallegos properly- it sounds like Gal-jagos but I’m not sure I have it right yet.

The scenery is amazing; I sense that further down towards Cape Horn it will be even more stunning. Already I am entranced with South America, and we have yet to journey into Chile, and on down to Tierra del Fuego province.

Patagonia is a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. According to Wikipedia, the name Patagonia comes from the word patagón. Magellan used this term in 1520 to describe the native tribes of the region, whom his expedition thought to be giants [2].

Some early archaeological findings have dated human habitation to between 8,000 - 12,500 BC. The historically identifiable indigenous ethnic groups are the Kawésqar, the Tehuelche, the Selk'nam and the Yaghan people. The Yahgan (also called Yámana), inhabited the southernmost part of Tierra del Fuego, and were, for a time, falsely considered extinct [3].

They wore little or no clothing, even in the harsh cold, at least until Europeans came, and were able to survive by several means, such as covering themselves in animal grease, huddling around small fires, squatting, and sheltering among the rock formations. Over time, scientists found that they evolved higher metabolisms than the human average, generating more body heat. The Chilean census of 2002 counted 1,685 Yahgan in Chile [4].

Ferdinand Magellan was the first European explorer to come upon Tierra del Fuego, and the first European to cross the Pacific Ocean and circumnavigate the world. King Manuel, of Magellan's native Portugal, refused to support his plan to reach the Maluku Islands (the "Spice Islands") by sailing westwards around the American continent.

Magellan left Portugal and proposed the same expedition to King Charles I of Spain, who accepted it. He set sail from Sanlucar de Barrameda in southern Spain in 1519, with five ships and 270 crew, and had to deal with a mutiny during a five month stay in St. Julian, (220 miles (359km) North of Río Gallegos), in which one captain was killed and another marooned.

During that winter, one ship was lost in a storm, and they found the passageway to the Pacific and entered it on All Saints Day, and so it was named, in Europe, the Strait of All Saints, later changed by the Spanish King to the Strait of Magellan (Estrecho de Magallanes). While exploring the passageway, another ship deserted, and eventually, under horrendous conditions, the remaining crew and ships found their way across the Sea of the South (now called the Pacific Ocean) to present-day Philippines, in 1521, where Magellan lost his life in a battle [5]. Fordham University’s Internet History Sourcebooks Project has a fascinating transcript of a Genovese pilot on board his ship, Trinidad, recording the voyage [6].

There was a general belief that Patagonians were giants, between nine and twelve feet in height, a perception appeared to be supported not only by Magellan, but by Sir Francis Drake (around 1577), and other explorers. Later accounts, however, appeared to refute these observations, though photos do exist, and the general belief persisted into the twentieth century. Several theories remain active [7].

The name for Tierra del Fuego, (“the Land of Fire”) was given by Magellan in 1520, believing he was seeing many fires (fuego in Spanish), which were visible from the sea. In 1525, Franciso de Hoces, the Spanish sailor and commander of the vessel, San Lesmes, first speculated that Tierra del Fuego was one or more Islands, and today it is officially recognised as an archipelago.

Río Gallegos

We deplane in Río Gallegos, and I learn later that it was a pivotal town during the Falklands/Malvinas war, and the location of A4 “Skyhawk” Squadrons of the Argentine Air Force, which operated from the Río Gallegos Military Air Base. Recently, an 1892 Scots shipwreck has been inaugurated as a war memorial [8].

I stay with the gear and Hugo goes looking for a courier driver and van to move everything into town to our hotel.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in Río Gallegos

The town, laid out on the Southern flatlands beside the River Gallegos, is cold and windy; I learn only on the return journey, from our broadcast director, Jon, that the last bank held up by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was in Río Gallegos. Jon read this out to me from a book on the plane back from Ushuaia to Buenos Aires.

According to Jon's book, they came to town and were regular pool players and drinkers at the British Club, which still stands today. When they robbed the bank and rode out of town, the locals only half-heartedly followed, as they had come to know them rather well. The two then took a ship to Buenos Aires and from there to Bolivia, where they met their fate in a shoot-out, but perhaps not the way the film suggested at the end, it was claimed in the book that one of them survived.

It's hard to be sure - Jon said the book was speculative; there are many myths and speculations around the two. One website notes that the Club was established in 1911, i.e., later than the date of the robbery, and “despite the Falklands (Malvinas) dispute, the Club continues to function…. a city ordinance of March 2001 designated it as a "historic place" [9]. Maybe the British Club was running before 1911.

The story, as recounted by retired U.S. Air Force Colonel Charles Callahan, is fascinating. Butch Cassidy and Sundance robbed the Bank of London and Tarapaca in Río Gallegos in February 1905, and almost certainly they were killed at San Vicente in Bolivia in November 1908. Apparently, they became ranchers in Rincon de Cholila, and rode the 600 miles (965km) return ride in two weeks, to rob the bank in Río Gallegos of $20,000 dollars. Four weeks later they abandoned their ranch, giving the sheep to the peons (laborers who had little control over their employment or economic conditions), and made their way, sometime later, to Bolivia. Butch and Sundance were never charged in Argentina [10].

We discover electrical and audio issues with our gear

We took two hours to get all the equipment from the airport into town to our Hotel, the Santa Cruz. It was freezing and blowing so strong we could hardly load the equipment onto a courier van.

The next two hours at the hotel were spent talking technical in Spanish-English and discovering several problems: crew allocations and transmission times; equipment movements; mic leads - specifically a connector wiring mismatch between my gear from the UK and local leads; power plugs - there are three varieties; and power distribution. I didn't have enough electrical sockets and leads for all our equipment, and some mic leads would have to be resoldered - some of the connectors had two pins bridged together that would need to be separated. We tested them hoping they would work, but no joy. One of Hugo’s crew disappears into town to the electrical store and returns with more electrical gear.

Time for dinner and getting to know Hugo in halting English, and I apologise for my poor Spanish. We talk of families and living in New Zealand, London, Australia, and Argentina. Hugo orders large platters of Argentinian steak and other morsels I won’t describe - they were all delicious. 28 hours without sleep after leaving London, sleep comes at 10.30 pm Sunday night 25th.

Monday 26th September 1994 - no transport to Porvenir!

We breakfast at 10.00 am - still talking technical and ways to solve problems. Hugo says his two satellite engineers, Patricio, and Hernan, arrived very early in the morning from Buenos Aires - 1,600 miles (2,560 km) by road, travelling night and day for the last four days, sleeping on the road in turn. They had a Ford pickup towing a 12ft (3.5m) dish - slow going in the wind and with such a low trailer.

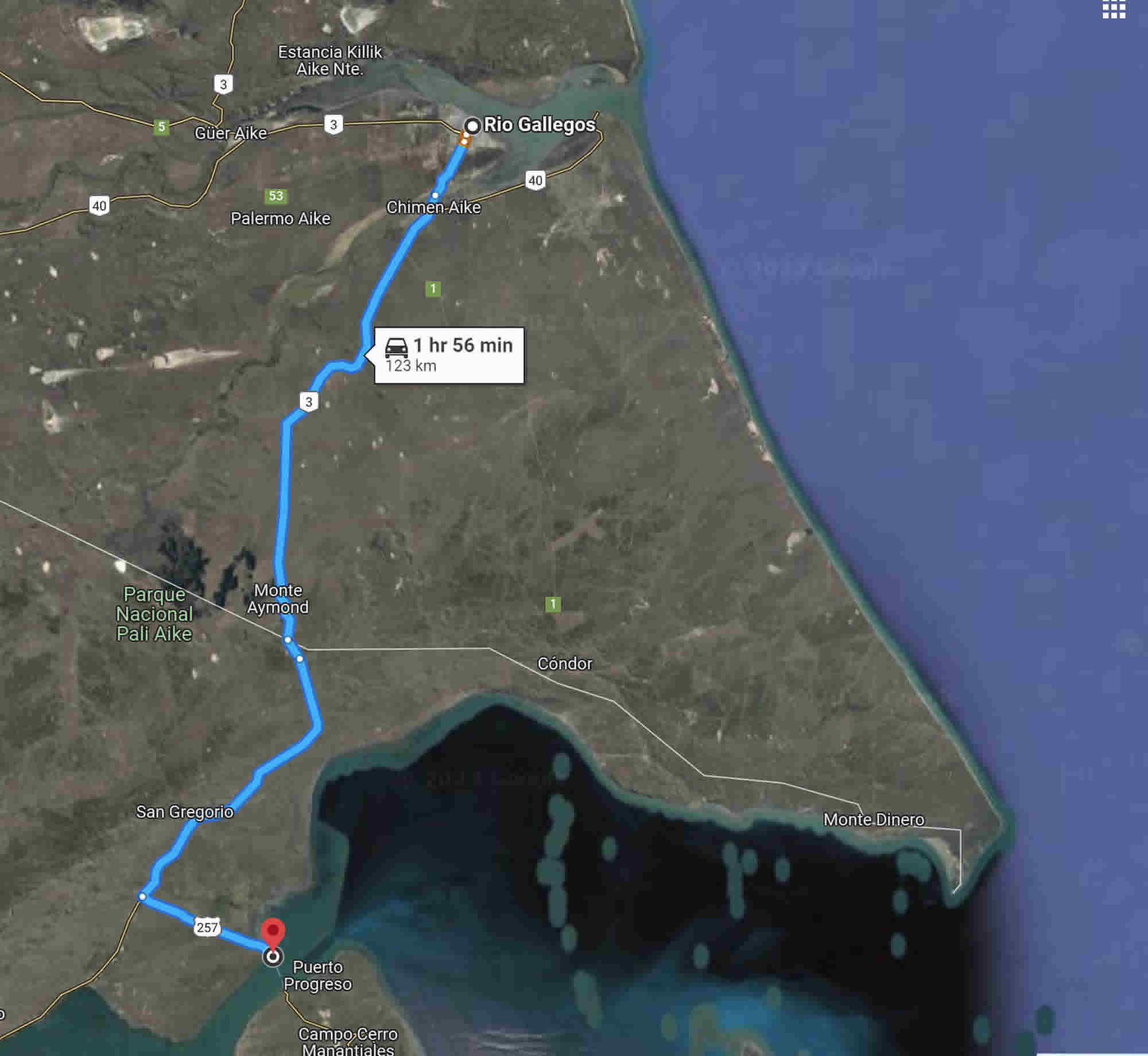

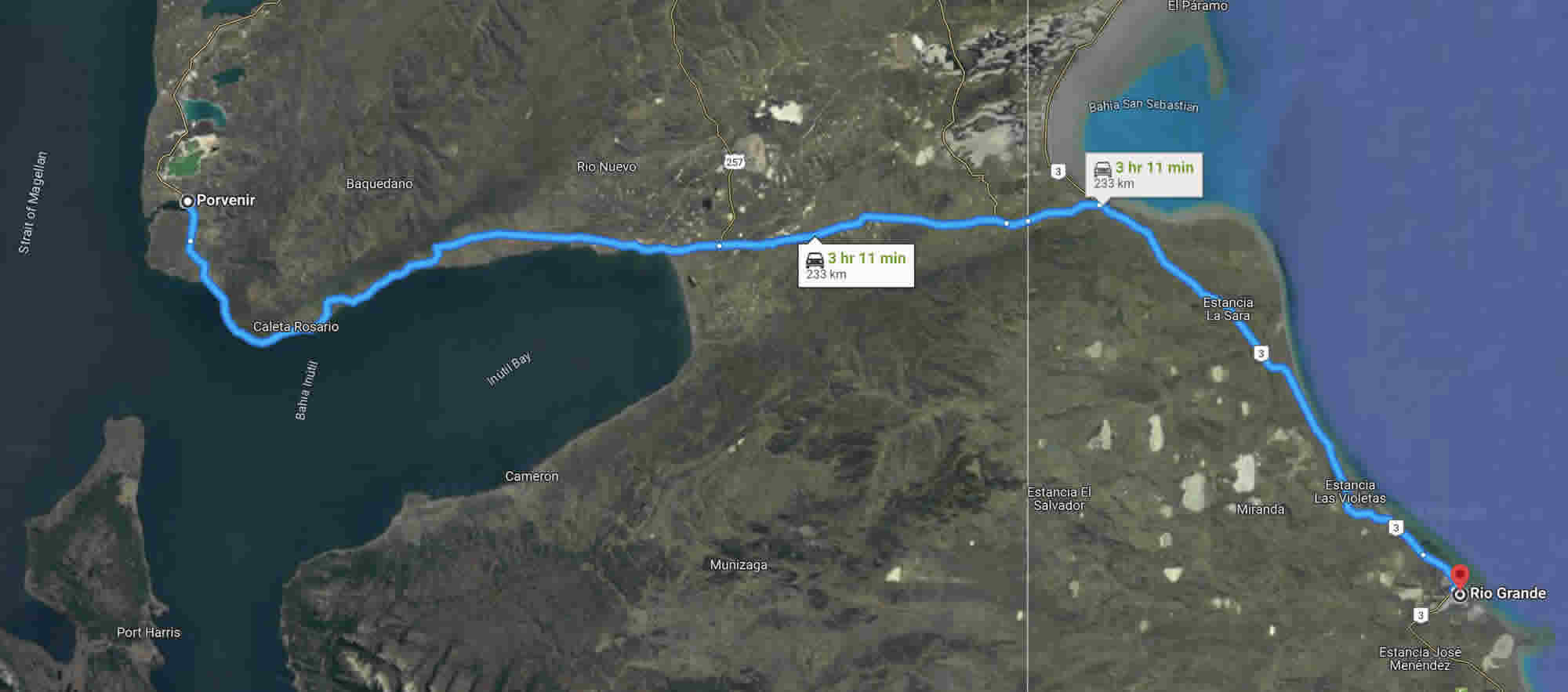

Hugo asks, could we not leave them to sleep until 3pm? I share my uncertainty about the road to Porvenir in Chile. We must pass customs and not miss the ferry 75 miles (122kms) away at Punta Delgada before midnight.

After calculating the time left to the first Transmission (Tx) - a day in hand, we agree, let them sleep until 3pm. Hugo needs to organise things in town; we'll meet back at the Hotel at 2pm. Only later, I learn that the truck arranged to get our equipment to Porvenir, and on to Ushuaia, had fallen through.

Time to go for a walk down main street, with the sun setting low beyond the land, and a harsh wind up, to send postcards to everyone - New Zealand, Australia, London. At 3pm Hugo returns to say he can't find a truck to get to Porvenir. We meet Patricio and then Hernan - both exhausted, and lunch at 3.30, talking for over an hour and going through the four uplinks and Tx slots from three locations and everything we need to achieve.

They are aware we need to get double equipment to the last site in Ushuaia and set it up - there's simply not enough time between the last two transmissions. I express my disappointment at not leaving Río Gallegos yet, how we must get through customs and not miss the ferry from Punta Delgada to Bahia Azul, to get to Porvenir in good time for the first Tx. Hugo and Patricio become animated and leave to find a truck. Hernan and I sit in the empty hotel restaurant and solder audio leads, rewire power plugs, and cable-test connections. Patricio returns with no luck and there's no sign of Hugo. Patricio and I leave to buy more power connectors. We return - still no truck and no Hugo.

At 9pm Hugo returns, and I meet Roberto who is to be my driver for the next five days. He speaks only one word of English - 'ok' (and I virtually the same in Spanish), but we still manage to learn quickly and talk about everything under the sun over the next five days. For his hire as a driver, including his van, I bet he wouldn't have believed what he was about to become involved in.

On our way, but stop and wait at Argentine Customs

We work solidly for an hour loading the pickup and van and say goodbye to Hugo - who must go back to Buenos Aires, and then we leave at 10pm only to travel a hundred yards and stop. What's happening now? Argentinian customs. We stamp about in the cold and wait for the inspector. I hand him my Spanish-written letter of progress from London, which seems to speed things up.

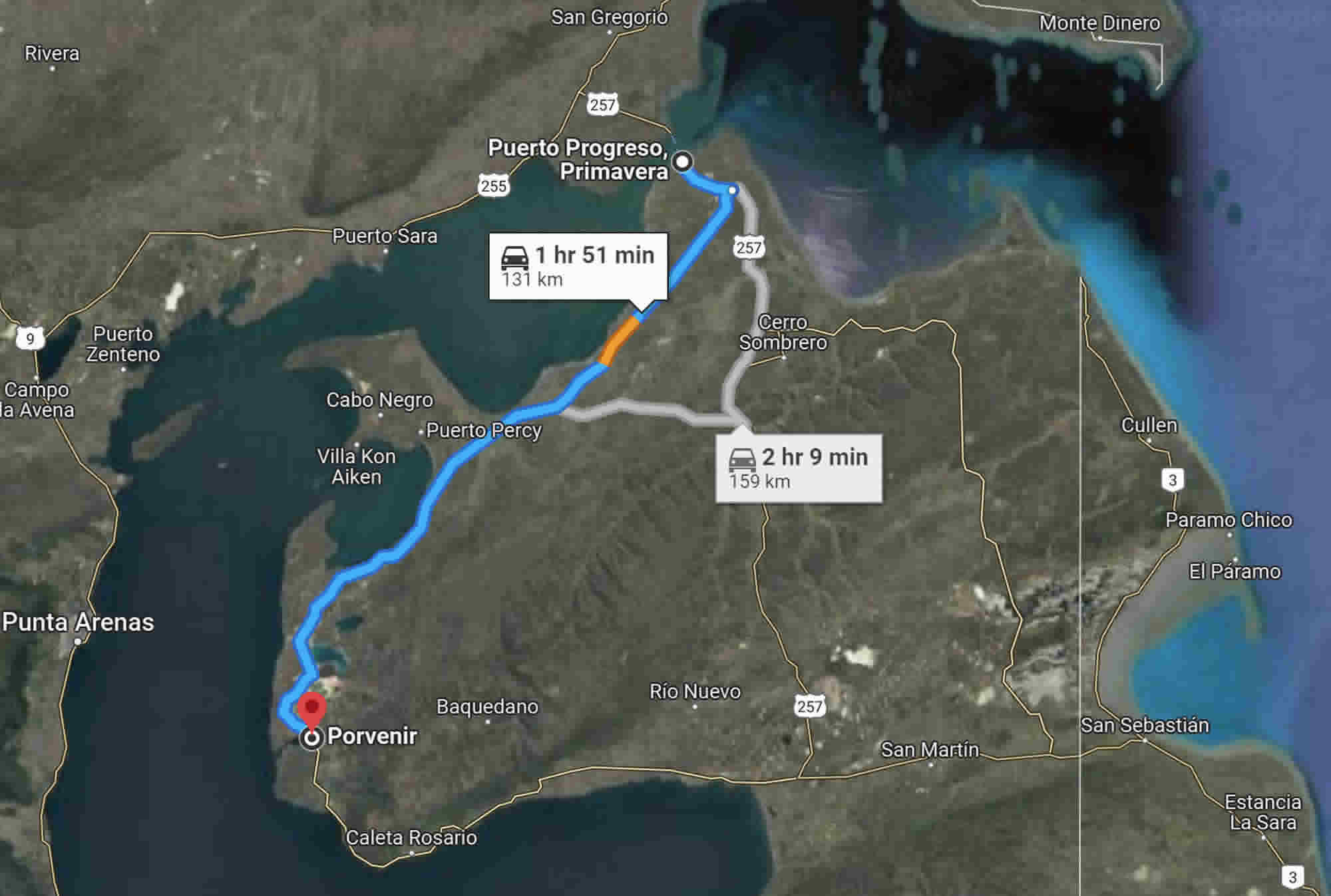

We must leave Argentina through their customs office just out of town, drive around 42 miles (68kms) to the border and enter Chile there through Chilean customs. Without the departure approved at Argentinian customs, there’s no entry at Chilean customs. Then we must drive another 34 miles (55kms) to Punta Delgada (on the North side of the entrance to the Strait of Magellan - the map shows Puerto Progreso on the south side), to catch the ferry before midnight, and push on to Porvenir, another 85 miles (136kms).

We don't hold out much hope but travel at great speed, almost recklessly, over dusty, and pot-holed roads to make customs, which we pass through with less delay than in Río Gallegos.

At 2.30am we call a halt and check in to a hotel which appears lit-up in the middle of nowhere - on the road near Punta Delgada; there's nothing else around for miles either side. It looks like a grand old silver mining hotel. No chance of making the crossing - it'll have to be the 9.30 ferry in the morning. The hostess gives us dinner at this hour, and we bunk down in twin rooms.

Miss the ferry!

Up at 8am for breakfast, Roberto and I play table tennis waiting for Patricio and Hernan to join us. Then we're off, arriving in time to miss the first ferry by minutes. I'm annoyed. Patricio tells me to chill - hey! don't worry, and tells me a joke s- - - happens! We laugh. It's minus four degrees as we wait on the shore and take photos, and then drive onto the ferry at 10.30am.

On the road now, a clear day all the way to Porvenir. The road is wild with a feeling of remoteness, and always the dish in front, eating their dust.

We pass elaborate entrances to seemingly nowhere, and see many sheep, stopping to chat to two gauchos on horses who ride up to the vehicles; they appear to be father and son. Patricio engages in a lengthy animated discussion, it seems to me, about life in general, nothing about directions or where we're going. I think, you're a gentleman, Patricio, his greeting and meeting sound, I don't know, honourable, courteous.

On we go. There are glimpses of the Strait of Magellan on our right. The VIPs will be coming across from Punta Arenas by ferry for the first transmission.

In recent times, around 1,500 ships pass through the Strait of Magellan every year [11]. It is one of the most difficult routes in the world to navigate because of its natural narrowness in places, the unpredictable winds, fog, and tidal currents; and so, maritime piloting is mandatory. There are 41 lighthouses along its 570 km length [12].

Arriving in Porvenir, Chile.

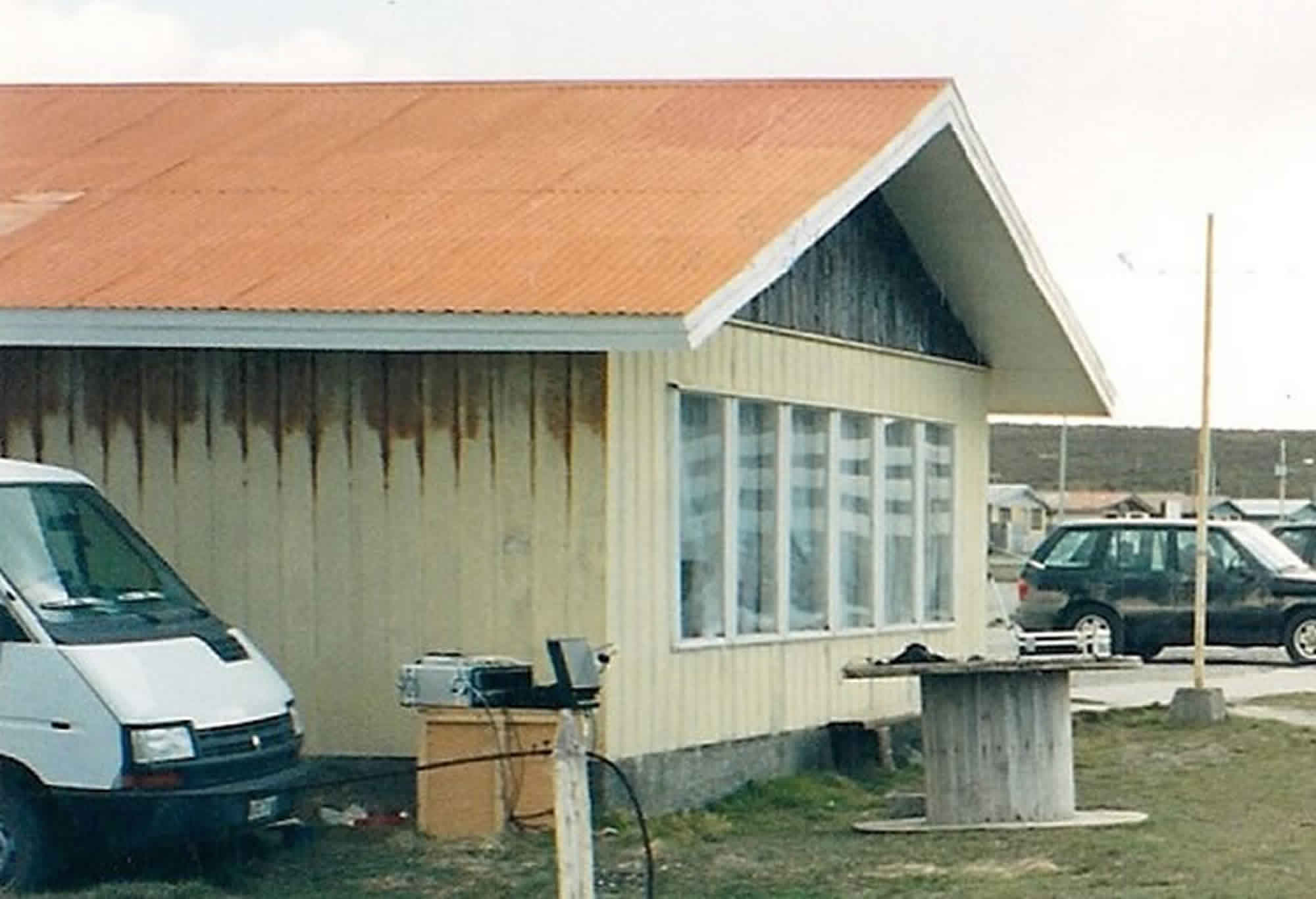

We arrive at 3pm, 10½ hours before the first Tx to London, scheduled at 01.30am local time, and check in to the Hotel Rosas in the middle of a pleasant and tidy town - Porvenir - pop. 5000.

Protocol is important - we meet the Alcalde

Patricio advises, we must speak to the Alcalde (the Mayor) - it is good for us to show respect, things will happen much easier. We walk to his office, and he meets us right away. Patricio speaks fluently and Senor Torres nods and looks at me. Can we get electrical co-operation? Patricio asks. Yes, replies Senor Torres and he picks up the phone. We appear to have become important people in his town.

We must now meet the head of the Electricity Board at the Gas Turbine plant on the edge of the town. Can we go there now? I shake his hand and we leave. It's now 5pm, 8½ hours to the first Tx. We still haven't found the location nor assessed what power is there. We go to the Gas Turbine plant and a young electrician agrees to follow us. On the way back to town the Alcalde's assistant proudly points out the town's new prison; for a town of 5000, he says they have five prisoners there. I wonder briefly in passing about statistics and population proportions. The town mayor and representatives could not have been more helpful to us.

Finding the first transmission location

We drive around and can't find the location! This is important: the first Tx involves playouts of camera-recorded tapes, due to be couriered to our hotel at 10pm by Courier from the VIP party travelling up North, on their journey to Punta Arenas, on the other side of the Strait of Magellan. From the dock, wherever it is, we'll also go live for the second Tx when they arrive on the ferry at 11am the next morning.

Four miles out of town we find the Dock and a small cafe - Penguido's. There's no other dock for 200 miles so this must be the one: Embarcadero Bahia Chilota - the Pier, alongside the Chilota Bay Artisanal Fishing Terminal.

We begin the set-up in the freezing cold but there's a barn nearby and the local owner is pleased to let us shelter our equipment there. This is good for the dish as the wind must be blowing 40 knots - it's fortunate we can align the dish to the satellite in the lee of the barn, partially protected.

I leave Patricio and Hernan to their expertise in aligning the dish and setting up the large amplifiers and other equipment, and go with Roberto to finish soldering leads at the cafe 30 yds away.

The lady is to keep the cafe open for us until 3.30am the next morning for hot coffee (though she didn't know it at the time). At 9pm there's still no power connection, the electrician having gone back to Porvenir for even more cable and connectors. Patricio also needs further connectors - he disappears into town to find anything he can. I ask Roberto to drive his van to the hotel to pick up any tapes that might have arrived from the VIP party by overland courier (the long way around the Strait and over the Punta Delgada ferry).

Not enough power!

There's no power for the Inmarsat satphones. We have two briefcase-size Inmarsat satphones - one for VIP audio return from the London studio, and another for the control channel to speak to various satellite master control rooms (SMCR) in Europe. The lid on each is the transmitter and receiver (the 'transceiver'), when opened and positioned to acquire a selected satellite, and they each have a long curly chord to a handset that has a keypad on the underside. (I’ll explain the audio and video paths below). No power, so out with the croc clips and connect to the Ford pickup battery; it means we must keep the engine running as the phone draws 13 amps and would drain a car battery in perhaps two hours.

I align the satphone transceiver to an Inmarsat satellite and call the London SMCR. They're ready to take our main satellite signal but we have no heavy power for the uplink amplifiers and so I advise of progress. The electrician arrives back and begins cabling from a power pole 50 yards away. We're three hours away from the first Tx time slot. At midnight we have power but not enough for all the uplink equipment, the satphone, plus all my audio equipment needed in the morning for the live camera Tx. The Ford engine runs for hours. When it stops for lack of petrol, we fill it from cans and start it again; the satphone is our only contact with the outside world and it's now dark, blowing about 25 knots and down to probably minus 12. We take turns sitting in the Ford cab with the heater on for a moment to get warm and then back out on the job.

Roberto arrives back - the tapes are here! I'm overjoyed. Hernan calls Madrid SMCR for Hispasat, one of the satellites we’re using, to set up the satellite transponder for our link to London. Hispasat receives our test signal and audio tone loud and clear - the question is, can London receive it as well? We phone London SMCR - no, they cannot receive us. We're using new technology - digital Spectrumsaver, which can, if required, squeeze multiple channels, through digitization and compression, into the same bandwidth as a normal (analogue) television channel.

In London, they cannot decode the signal we're sending. We spend two hours on the satphone to London and Madrid trying to find a solution to get the signal to London. David - our main contact engineer in London, and his team, are pulling out stops to make it work. He has had hardly any sleep as well – they've been working all hours, taking in feeds from five other locations around the world for the same epic event.

Cannot broadcast, time to call a stop for sleep

It's now 3.30am - 19 hours without sleep for the second time and another Tx at 11am, if we can get it working. I must call a halt - the team needs sleep and there's no way we can transmit to London. I call David in London and agree with him to power down and discuss a possible time when we can test next morning. I tell the crew not to worry, we know at least the signal is leaving Porvenir and reaching Hispasat (as Madrid Control confirmed).

Cold and tired, I call our Head of Business Services in London, wake him up, and detail our options. We know that London will move heaven and earth to receive the signal there. We call Hispasat in Madrid to notify them we are powering down the uplink to their satellite transponder, and then turn off all our equipment. In the freezing cold we are constantly jumping, running on the spot and waving our arms to keep warm. The equipment must be partially dismantled and put in the barn because of the weather. At 4.30am we drive to the Hotel in town. Senor Rosas has provided snacks in our rooms and is uncomplaining at this hour.

The next day setup to broadcast, hoping it works

I'm up first at 07.30am after 2½ hrs of restless sleep and rouse the others. We have a quick breakfast and talk about anything but the problems. We learn jokes from each other's country and there's general laughter and shrugging of shoulders. Hernan translates for Roberto – the humour is not language-bound. We drive back to the pier and it's much easier to turn everything on this morning. Leaving Hernan and Patricio at the dish, Roberto and I position his van at the Cafe with the engine running for the second satphone.

We must use every bit of power we can find from the cafe for the rest of the equipment. The Pickup is running to provide power for the control satphone near the dish. The van is running near the cafe for the VIP satphone, in turn connected to my wireless transmitter for the headsets and earpieces that the director, VIPs, and crew will use to hear questions asked from London. The VIPs will then respond on camera, and their audio and vision will go back to London via the main satellite path. We need one more power outlet and connect the talkback equipment to the only one left in the cafe and hope for the best. It's a little dodgy - the socket is almost hanging off the wall and I gaff tape it back in place.

The camera location at the jetty where the ferry will dock, is around 110 yards (100m) from the dish. We run out 2 audio and 1 vision cable to connect the camera kit. With under three hours sleep, we don't even know yet whether London has sorted out the problem but must continue as though they have. It's not worth calling them until we're ready to send.

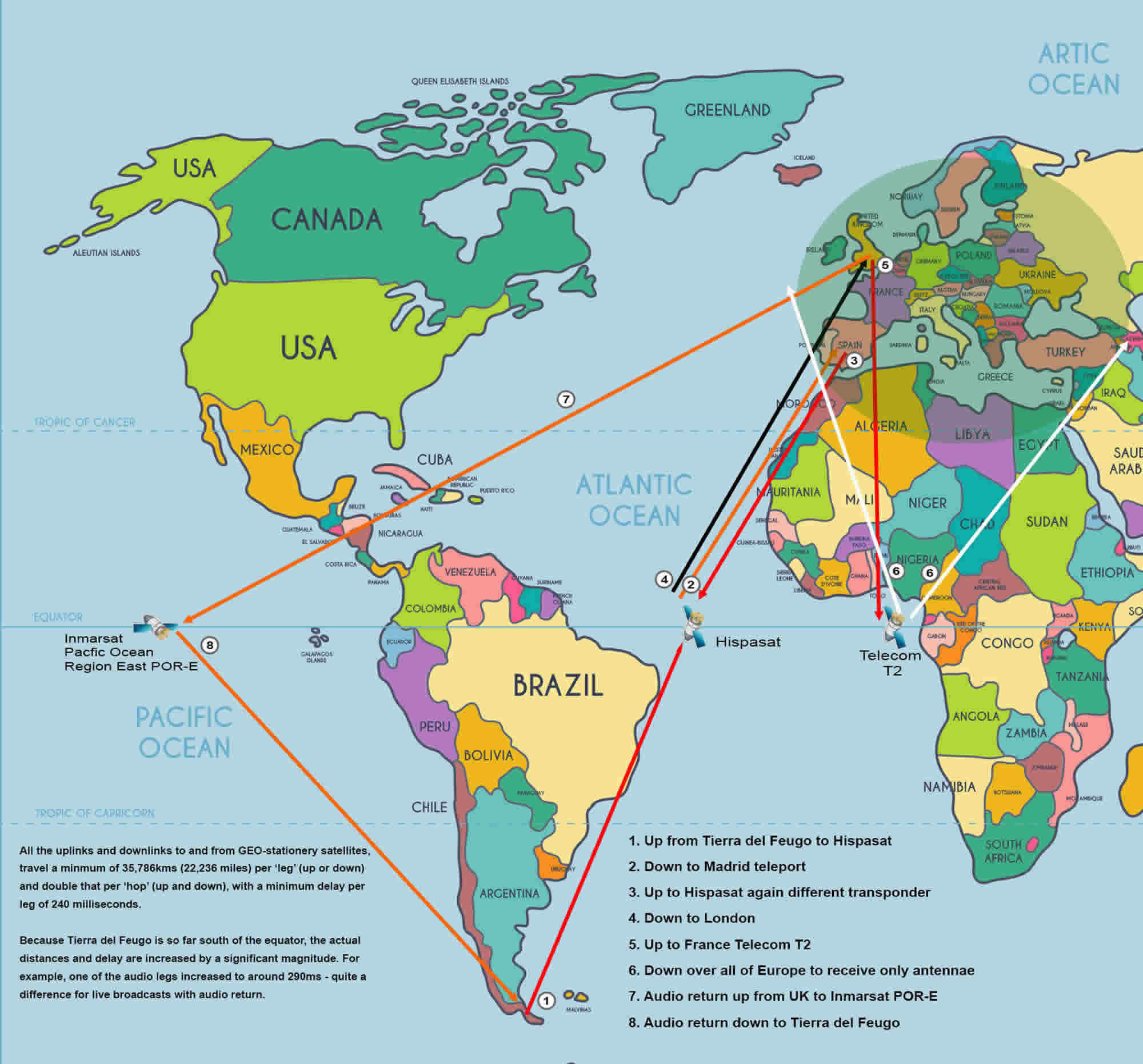

Pause for a minute to explain all the signal paths

The signal path can be explained as follows: The camera vision and audio travel from the Porvenir jetty camera and audio equipment, 110 yards down the cables on the ground, to the uplink equipment at the dish. These signals are then digitised, combined, and uplinked to Hispasat (see (1) on the diagram), down to Madrid (2), up to Hispasat again on another transponder (3), down to the London satellite master control room (4), and on to the London studio (Mission Control). There, the signals are mixed with studio input, then sent back to the SMCR, up again to another satellite - France Telecom’s T2, (5) and then out to receive sites throughout Europe (6), for invited audiences watching the event. The audiences will be seeing live broadcasts from the London studio with an anchor personality and guests, mixed in with programming from the six locations around the world (some will be live like ours, some were pre-recorded).

All the uplinks and downlinks to and from geo-stationery (GEO) satellites, travel 22,236 miles (35,800kms) per ‘leg'. A leg is one up or one down to a GEO satellite, a 'hop' is both the up and down together. The key issue is audio delay which is a minimum of 240 milliseconds per leg (a time length that can be perceived by humans) or double that for an up and down hop. Because Tierra del Feugo is so far south of the equator, the actual distances and delay are increased by a significant magnitude. For example, two of the audio legs (one hop) increased to around 290ms delay each - quite a difference for live broadcasts with audio return.

The audio (questions etc) from the London studio out to the VIPs, travels a different route. To receive the audio in our earpieces in Porvenir from the London studio, it is mixed in the studio and sent to the SMCR in London, out to a local telephone exchange, long distance to an Inmarsat Earth Station, up to an Inmarsat satellite (7), down to the satphone transceiver in Porvenir (8), in to the audio console, mixed to the radio transmitter, and out to radio earpieces for the VIPs, and headsets with mics for the producer, cameraman, soundman and myself.

The two satphone transceivers had different functions: The control satphone at the dish was only used for communicating with the satellite master control rooms. Bringing power up and down to an expensive satellite in the heavens from a field uplink requires extensive coordination and communication, so we couldn't use this satphone for camera production communications with the London studio.

Before going live, when the VIPs respond to camera with their audio going back via the satellite uplink, we could use their incoming VIP satphone to communicate with the studio. I mixed the VIPs out from hearing this production chatter until close to going live so they didn't need to hear our comms, but then just before live they were mixed in so they could hear the London studio control room giving them cues to standby, and then hear the questions from the studio. It is called IFB (international foldback).

Mixing the audio was relatively plan sailing once operational, it was the setup itself, and the testing in each location, that were challenging. One surprise was the range of reception for the radio earpiece receivers, they worked very well even in windy and cold conditions.

During tests, the Porvenir crew receive their local audio returned back from London, but this is mixed out during broadcast so that we wouldn't hear ‘doubles’ - the actual spoken words, and the delay repeats. Through cable and space, the audio from Porvenir that I hear back, travels over 114,300 miles (184,000kms) to return to my headset with a 1½ second delay - the equivalent of 4½ times around the world. This is called 'programme return' and allows the VIPs to hear and respond from a remote location, to studio questions asked in London, and then broadcast that out to an audience throughout Europe in real-time.

It works! - or so we think...

At 10am we're ready to send audio tone and colour bars (test signal) to London, only one hour before the scheduled live slot. I call London - they've pulled out all the stops and are receiving the signal! (how they did it is explained below). I'm amazed - the signal path is not direct up to Hispasat and down to London as originally planned - as explained above, it's a double bounce: up to Hispasat, down to Madrid, up again to Hispasat on another channel, and down into London - they've worked wonders in three hours! We can't stop to be happy as my kit has an earthing problem - Billy puts his electrical meter on it, we float the earth at the last moment and in trepidation turn the power on - it's not an optimum solution, but it works.

There's a satisfying glow of 'on' lights but there's no time for more tests, we look up to see the ferry has crept in behind us and is about to dock. Action stations! I open up the mix to the earpieces on the audio console, then run to the ferry location with the VIP earpieces and production crew headsets.

Jon Lane, our director, comes straight off the front of the ferry and over to us. I didn't get to see him at Heathrow on the journey out; the last time we met was in a meeting in London two weeks before. How to explain we were unable to play-out any of his pre-shoot material to London the night before? He's disappointed and takes some minutes to think it through. He's a professional though and agrees that 'these things can happen'. It means a re-think on the script he's developing in his mind, and immediately he gets down to working out different possibilities. London studio comes on in our headsets and says we must go live now - no time for getting any tapes played out first.

Live – the first satellite broadcast

We scramble. I wire Sir Robin and he stands ready roughly 110 yards (100m) away from the dish, looking to camera, and then I race back to the sound mixer by the restaurant. London Studio crosses to us live but there's a problem. SMCR tells me they have pictures but no sound. London diverts to a studio interview, and shows our video on a large screen in the studio as they wait for us to fix the issue.

We're frantic - I leave the mixer and run to the ferry and ask Nic, the soundman, can he send tone? Yes, he says. The tone comes back into my earpiece from London as I check the cables right there with him … but it’s intermittent!

We start checking cables. There's a 1½ second delay between plugging and unplugging cables and what we hear back. When I plug and unplug one audio cable, the tone appears to be noisy right at the connector - the problem is in the cable! There's no time to waste. I look at Nic and we ask each other... chop? Out with the cutters and chop the audio connector off. While I'm stripping back the wires on one end, Nic takes the cutters and chops off the connector on his audio 'fly' lead. We joke about broadcast standards in the field - any connection will do at a time like this. We twist the correct wires together. No joy! expletive! Robin is turning blue in the harsh wind. I run 110 yards to the dish with London studio control room animated in my headset. A second seems like a minute as the London Studio presenter stalls with additional words, asking us whether we are there yet.

At the dish, Patricio is on the satphone to Hispasat control in Madrid. We check all the audio connections, repatching different combinations, taking connectors apart to check the soldering, coming to the limit of what we can do. The audio LED light on the Spectrumsaver input seems to glow - it's hard to see in the daylight if it shows any signal at all. I cannot get back to the camera location in time, and I'm out of range to Nic's camera talkback. Is Nic still sending tone? What to do... London can speak to Nic at the camera location, and they can respond back to me.

Patricio hangs up his satphone to Madrid satellite control and passes the handset to me. "I can call them back" he says, "call London". I call London and ask them to ask Nic to confirm he is still sending audio tone, marveling at how the request gets to Nic 110 yards away from me, via London. Yes, London says, Nic is still sending tone. (They couldn't hear the tone in London, they simply asked Nic to confirm he was sending it). I hang up and Patricio calls Madrid again. I look at the Spectrumsaver LED's - we have audio signal! but... London still does not. An expletive of sheer rage. The audio signal suddenly bursts through, with the Spectrumsaver audio led light showing a strong signal, and Patricio gives me the thumbs up - a faulty connection in Madrid, he says later, nothing to do with us. It’s not uncommon though.

We're live! I run back to the mixing desk to check everything is ok, and then sprint back to the camera with a thumbs up to Jon from the distance, as he nods, and I hear the first question to Robin from London in the headset, loud and clear. When I get there, Robin is answering. He speaks and when I hear a low-level mix of his first words come back through my headset 1½ seconds later, it's sheer bliss! The local audio is quickly mixed out of the return and then all we hear in the headsets is London studio audio and Robin talking locally. Now we're working on adrenalin alone. Later, London tells me later to stop shouting into my headset microphone and distorting it. I tell them I was running, and it's easy for them to say, in a warm, windless London SMCR. Sir Robin does a star turn - the sheer difficulty of getting live out of Porvenir in freezing 40 knot winds and all the problems add to the impression of exciting, live television. The wind is really kicking up. The camera shot is a good one, tight on Robin, the ferry, and three SUVs in the background as they come off the ferry. I wonder whether London can sense the ruggedness and wildness all around.

The other VIPs join for a group piece to camera and then it's all over! They retire to the warmth of the café, full of people who have come out to sit and watch. Jon and I start plotting which tapes to play out in the time left of our Tx slot. The main party prepare to depart, and Jon leaves the tapes with me. It's now 12.30pm and the crew play out tapes for another hour and a half, to be edited in London.

What really happened?

For the technically inclined, this event took place just prior to the released international standard for digital video broadcasting by satellite (DVB-S) in 1995, which mandated a MPEG2 transport stream (Motion Pictures Expert Group), and set in motion the virtual explosion of digital satellite transmission technologies thereafter. Previously, analogue signals took a full satellite transponder, normally around 36MHz. I recall in London the engineers did tests for half-transponder and quarter-transponder digital transmissions, and marveled at the quality of the transmissions, especially the relative absence of ‘peak white’ artifacts left onscreen from fast moving images such as national basketball association games, transmitted for test purposes from the USA into our London control room. There was a general sense in the control room that we were looking at the future of broadcasting.

Nowadays, a typical satellite transponder can contain 8-10 digital television channels, or even more. At the time, we should have been able to uplink from South America to Hispasat, and directly receive that signal in London, avoiding the additional downlink to Madrid and back up to Hispasat. The digital encoder model used, the CLI Spectrumsaver, was very new, Madrid had a decoder for it, but as we discovered, London SMCR had an issue with their decoder, and apparently their spare was also faulty, so they did not have the means to decode the signal.

If I had packed a normal analogue television encoder with me, (in PAL - the European broadcast television standard), ‘in the clear’ that is, unencrypted, and, subject to finding a full transponder Tx slot, we could have uplinked directly to London and solved the decoder issue encountered. The signal had to come down to Madrid and be decoded first, then sent up to Hispasat in PAL format so that London could download it. I only learnt that this is how the issue was resolved after I returned to London from South America. But there were two issues: a momentary audio plug (‘patching’) issue in Madrid, which is not uncommon, but just so happened at precisely the wrong time, and the larger issue of decoding the complete video and audio signal, which by then had been resolved.

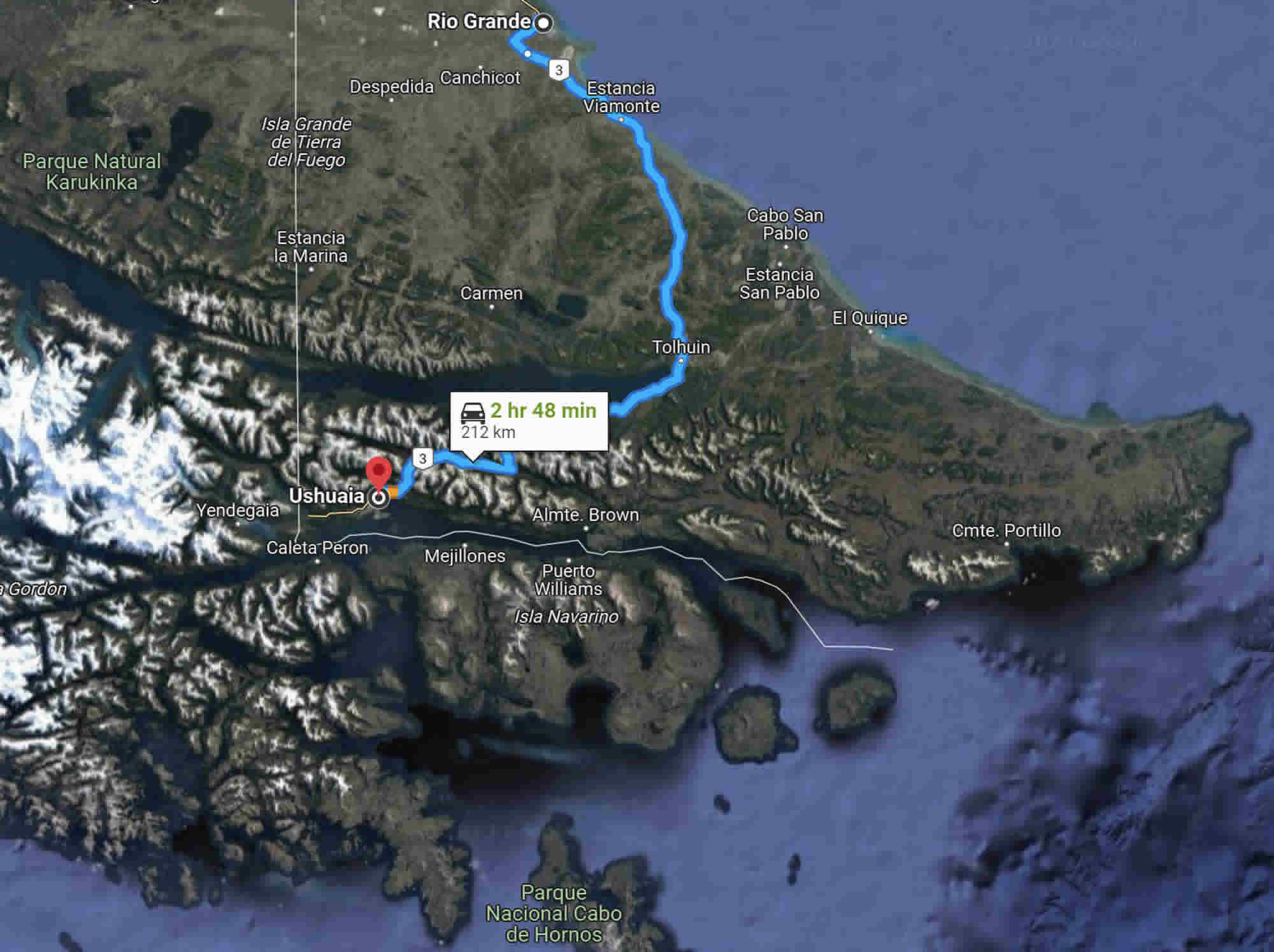

Pack up and on to Ushuaia – 272 miles (438kms) South

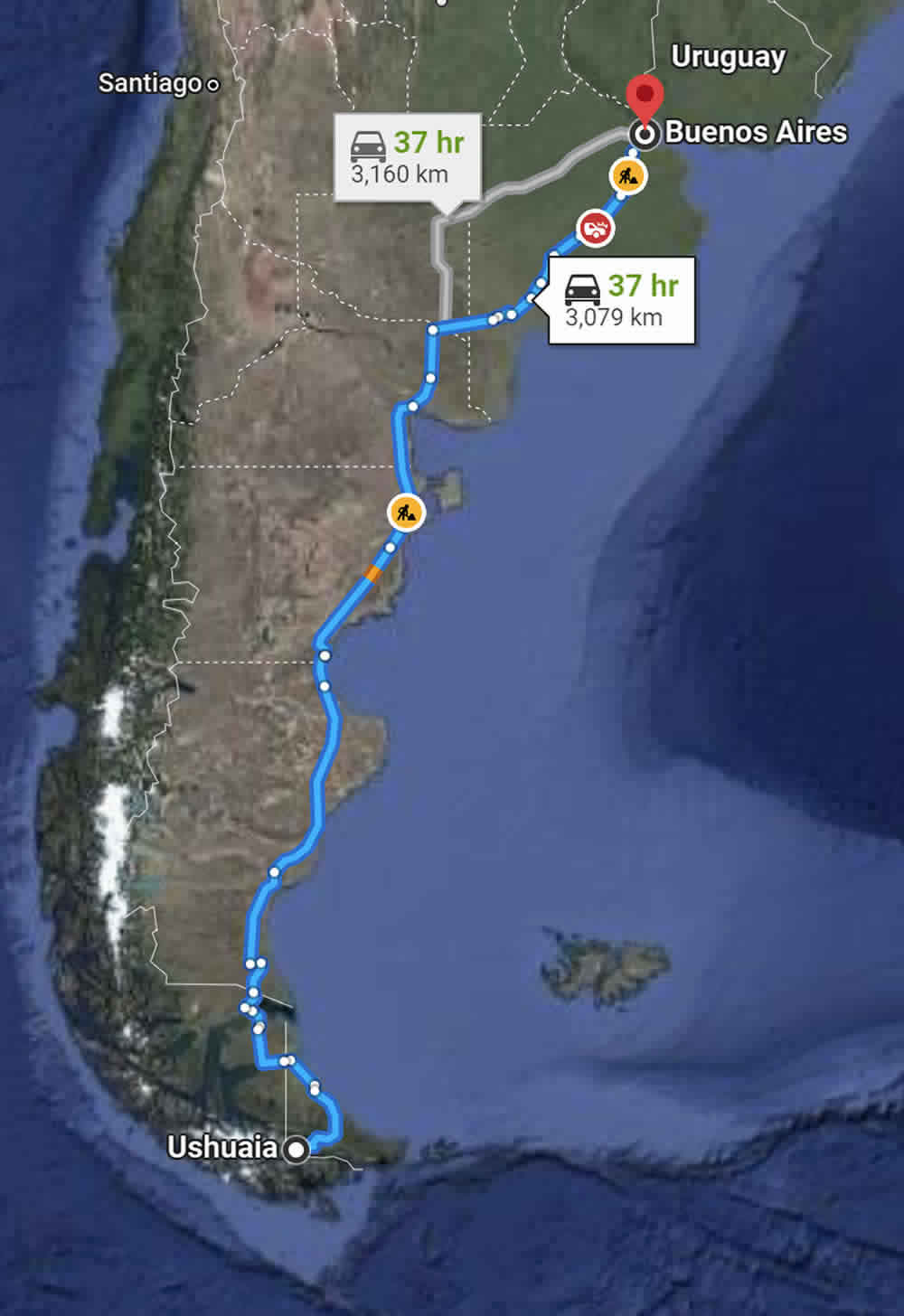

The event was over! The VIPs, production crew, and SUV support personnel, leave to drive to Río Grande and overnight there, 139 miles (223 km) away.

We will pass through Río Grande late that night and leave the trailer there with the satellite dish, for Patricio and Hernan to pick up on their way back (there's another one waiting for us down South). And then on we will drive to Ushuaia, 272 miles (438kms) from Porvenir. The crew is very tired and we pack up until 5pm in the bitter cold.

I thank the lady at the cafe and leave a good tip for her. She beams in embarrassment. We retire to Hotel Rosas in town for a shower and food. Patricio tells me over dinner he lost his best friend in the Malvinas/Falklands war and there is pain in his eyes.

Our Ford pickup and van entourage leaves at 6.30pm. Hernan forgets to pay for petrol and must turn around 10 miles out. They'll come after us if we don't, he says. Roberto drives on to the barren border crossing into Argentina and we wait there. The border is dark and remote - there are guards with machine guns and all our paperwork must be correct. Patricio and Hernan arrrive and everything is in order. We drive on through the night, stopping at Río Grande for a meal and coffee, exhausted. The city is amazing and silent at night with light winds and snow flecks falling.

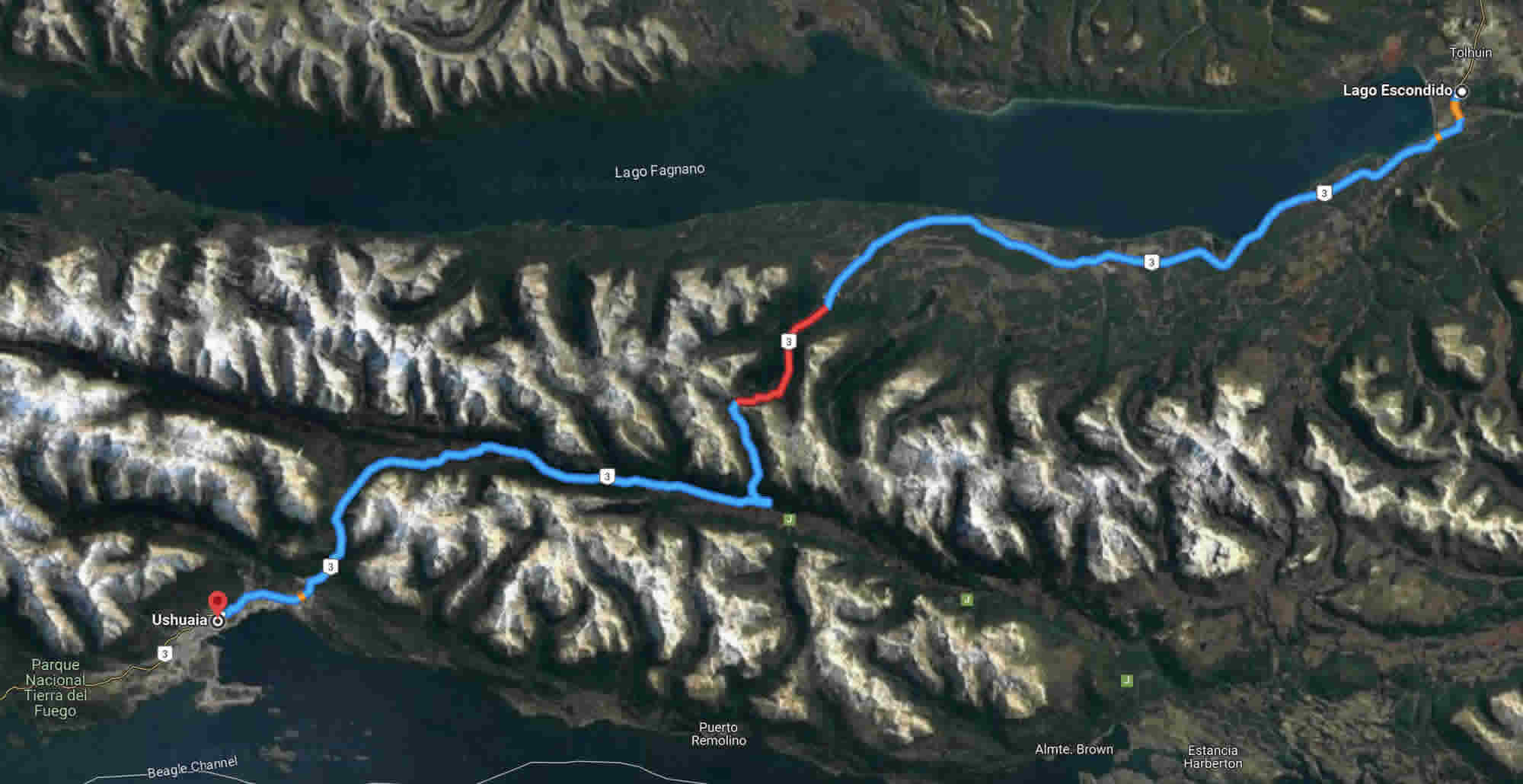

Roberto and I follow Patricio and Hugo in our van. Nobody sleeps during the drive - the road is good for a while but dangerously icy, then abruptly turns to mud holes and deep cracks, dusty one minute, then wet; it seeps into our skin. I drive from Río Grande to spell Roberto, until we hit the snow again at the foothills of the Andes, some miles from Ushuaia, near the point where the road meets Lago Escondida. I can't recall when I've concentrated so much, driving RHS 80mph (130km/hr) and the road is like marbles and then mud holes. The scenery we can just make out is awesome.

Over the Andes and down into Ushuaia

The road up through the Andes and down into Ushuaia is unbelievable. We're not towing the dish now - a very good decision as it has a low base and would not have made the journey, though originally planned. We are carrying over a ton of equipment still. Another fixed (larger) dish is being set up in Lapataia Bay as we drive. The snow is really coming down at the end of the journey, as we travel up over the Andes in the dark and down into Ushuaia. As we climb, hundreds of feet below there are sparse lights and looking down, we can just make out houses way below us that seem far too close to the side of the road.

The final leg through the pass from Lago Escondido, via the foothills of the Andes and down into Ushuaia, is magical in the early morning, from dark to dawn.

We reach Ushuaia at 05.30, now 21 hours without sleep for a third period in a row and with only 12 hours sleep in total since leaving London.

Ushuaia is beyond awe-inspiring for words. I was too tired to take photos, but I recall the snow had lifted momentarily with a pink hue at sunrise, behind troubled clouds, turning to a deep fog and rain again, on the verge of snow. Here is a more recent shutterstock photo of Ushuaia; the weather was coming in though, within two hours the rain and snow had set in, but even then, it was still magical.

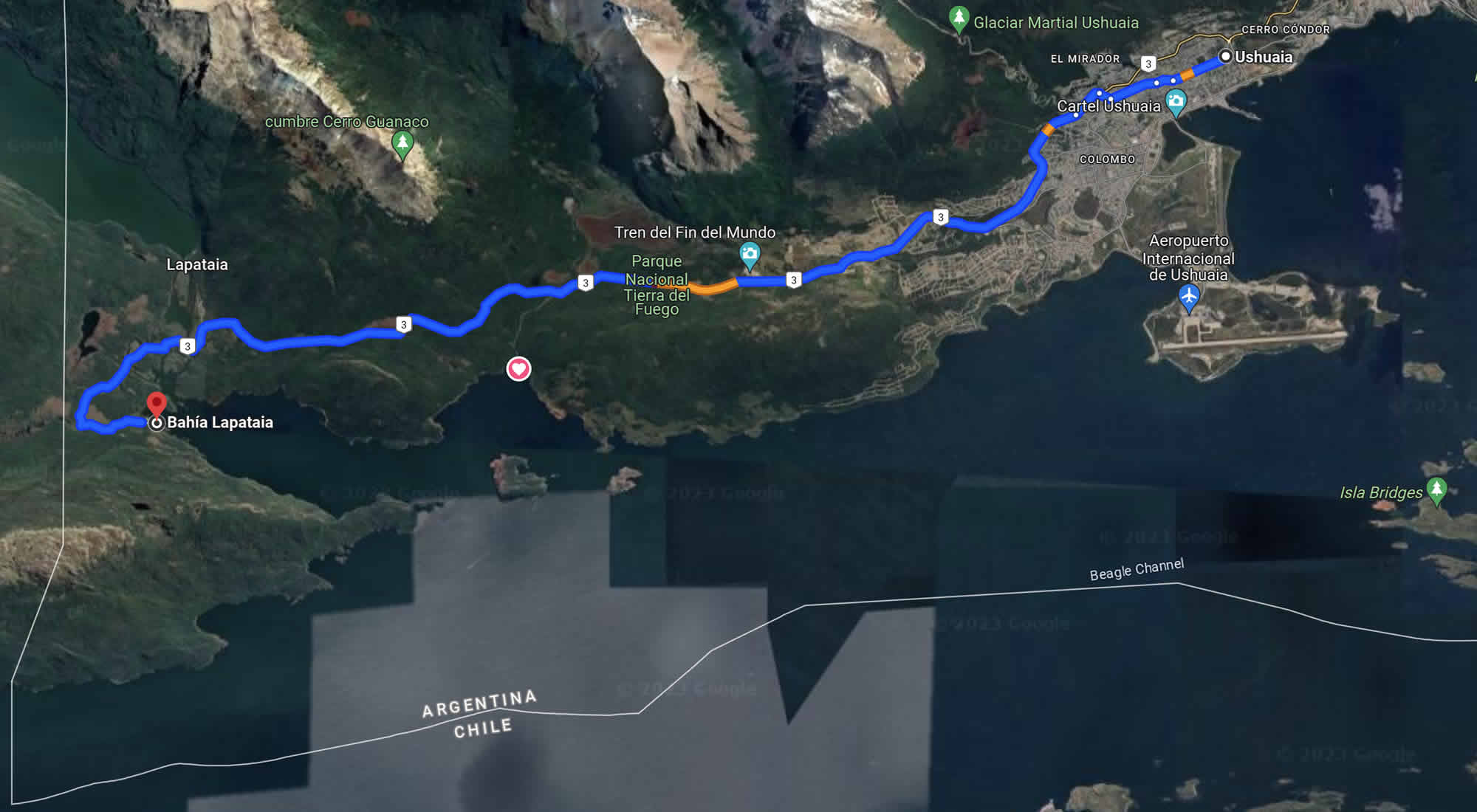

Two hours sleep then on to the next satellite broadcast

We book into Hotel Albatross right on the pier in the centre of town - perfect! I meet Patricio's brother, Billy, and Santiago, in their room. They are just waking up to go 15 miles (24 kms) out to the next Tx site - Bahia Lapataia Bay, the end of the Pan Am Highway, which runs somewhere around 15,000 miles (23,500 kms) from Alaska to here, except for a gap of around 66 miles (106km) between northwest Colombia and southeast Panama, called the Darién Gap. The distance has changed over time with various changes to the route.

We talk for an hour and go through everything we need to do. Billy doesn't quite believe me yet - he's done all this before with the Camel Trophy, and actions speak louder than words. I decode Patricio's words to his brother – he's ok! we've worked side by side for the last three days, this is what we must do!

Billy and Santiago leave for Lapataia Bay. We sleep for two cruel hours and breakfast at 08.30. Patricio, Hernan, and I are speechless with exhaustion. We've spelled Roberto at various times to sleep, as he will be doing the bulk of the driving today, and thankfully he's a little better but still tired.

Drive to Lapataia Bay – the end of the North American highway

We leave for the site at 09.00. Roberto puts on up-tempo tango music, and teaches me the chorus, so we sing and swing in laughter to keep our spirits up. The road is no more than a dirt track in places.

The road from Ushuaia to Lapataia Bay

We drive past the golf club, unlikely to be open at this time of year, but it looks like an interesting course along the river, and the rugby club. I recall thinking they must be hardy folk down here. The road was treacherous, icy, and we were sliding left and right, taking it slow.

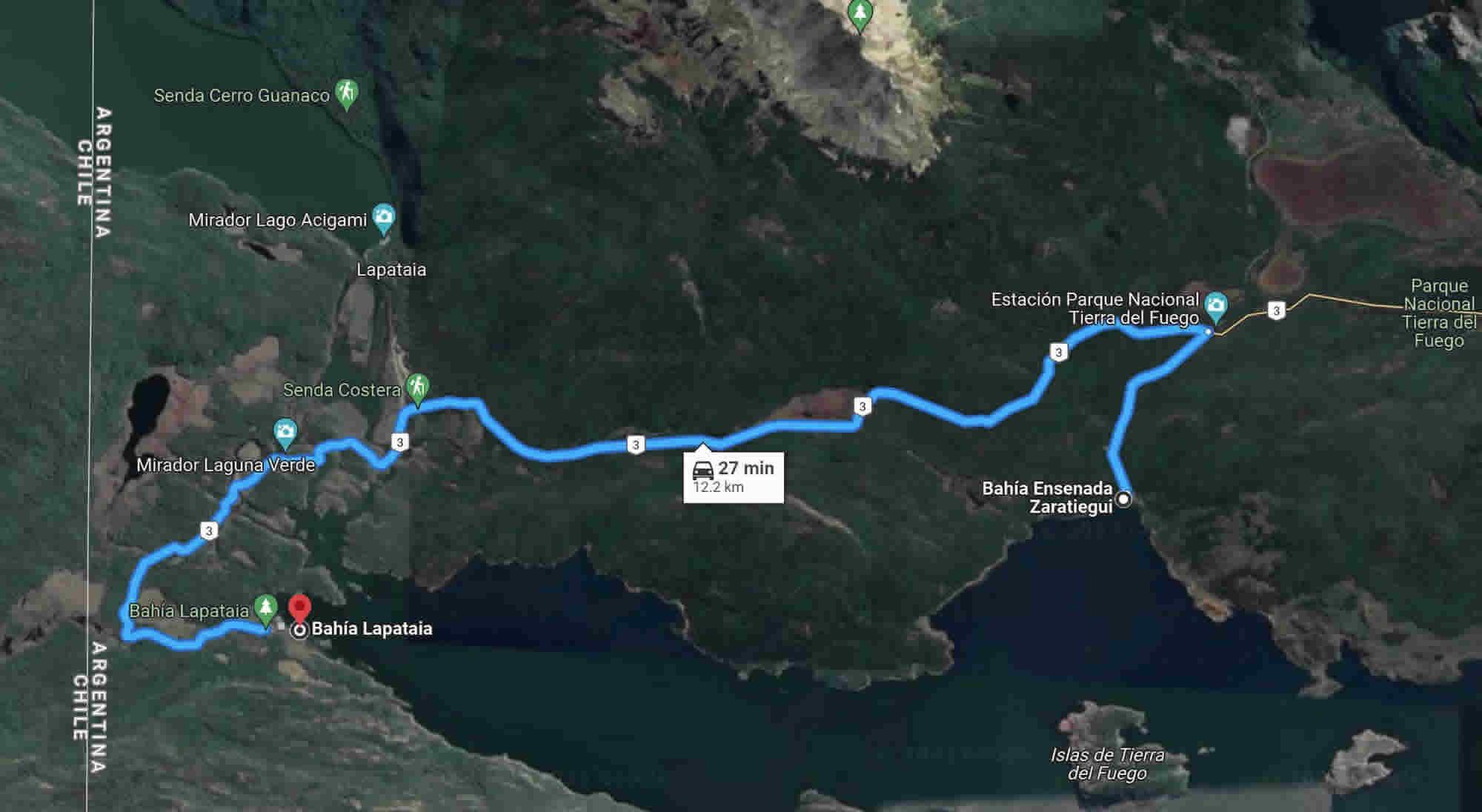

When we reach Lapataia Bay I cannot believe my eyes. We're so far South, the dish must point virtually straight ahead to reach the equatorial, geo-stationary Hispasat. It's the only satellite that can get us out of there. Looking at it from behind, the dish points straight into the mountain. The snow and fog coming off the mountain will be a major factor in whether the signal can get out of there, up to the satellite.

The satellite engineers had carefully measured this on maps in London, as we discussed it with our partners at Keytech, on the phone from Buenos Aires. In these meetings, our engineers had taught me the rudiments of what a link budget is, how to calculate the signal strength from, and to, anywhere in the world.

The link budget was a calculation process to output a figure of merit, 'G over T' or G/T. Measuring and calculating the link budget meant finding out the system Gain over the noise Temperature, taking all of the signal path, including the amplifers, various components, transponder power, transponder beam width, system noise, location, and the weather, into account. The calculations were complex, and influenced the choice of everything from the power of the amplifiers, to the size of the dish.

We found, when plotted on a map, that the line-of-sight to the geo-stationary satellite would just clear the front slope of the mountain with an acceptable fade (weather) margin, and the calculations were fine – but the weather was always an uncontrollable factor. Right now the mountain is covered in thick fog, with snow being pushed off the front face in the high winds. Patricio says relax! - Billy is a magician with these things.

There's no option but to start setting up kit. I place the control laptop satphone on the van roof to get a better signal. Billy bumps it and the transceiver comes crashing down into the snow. We fear the worst. There's nothing broken though and after picking it up and brushing the snow off it, I re-acquire the Inmarsat satellite for control and leave it on in case London calls. Between us though, the ice is broken - he repeats Patricio's joke "s––- happens", and from then on, we work and communicate with laughter and the job cracks on.

Power problems again!

I set-up the audio IFB mixer and VIP satphone and power them up. Plugging into the power generator in Billy's van, I get a strong earth off the IFB equipment chassis, it jerks my arm and launches me backwards into the snow. Damn it! - I lie there stunned, exhausted, rubbing my arm, unable to get up, and Billy comes and pulls me up, looking into my eyes to see if I am ok. I nod back, shaken, furious with myself, saying to myself in exhaustion, dumb! stupid! respect power! (I said a lot of other words too), and I stand there rubbing the jolt out of my arm. I think to myself, be careful! mistakes happen when one is so tired, be methodical, and don't rush.

Time to check the connections - snow has drifted on to one of the plugs, telling myself over and over, I can't make a single mistake with power. Dry it out, check everything and re-insert - doing it all slowly, by rote. No power still. This could blow the whole IFB talkback link to London - I throw the lead into the snow in disgust. Our VIPs will have to talk with no questions from London...maybe.

My mind is racing with the options - we could use the mobile satellite phone we had with us as backup. It was a very early version, I think it was a Motorola Iridium, not available to the public yet, but I can’t recall now - it had a long, thick antenna that could be angled, and it was heavy. I was to use it only if all else failed and London needed to get hold of us, very expensive per minute. Nokia actually made the first satellite mobile phone call in 1994, and Motorola Iridium did not launch publicly until 1998 after a ten year research and development effort, and promptly went bankrupt a year later. [13] Nevertheless, I had been given a mobile satellite device that did indeed work. I recall my boss saying to me in London that they were very new and not available yet.

Maybe the VIPs could hold the mobile satphone up to their ear during the shot, and hand it around - not pretty... I hope against hope it's only the fuse in the power lead, not the equipment. I re-plug with another power lead and yes! power to the unit. Then I pause for a minute and stare at the snow, reflecting on how close we've come several times over the last few days to not having a show at all. Billy looks at me and says our shared joke again. We laugh. Get on with it!

VIPs arrive - no signal

We call Madrid - they're getting nothing at all. London phones in - it’s Fabio from London SMCR! - bless his soul, he's been trying to get us for an hour and is relieved we've made it. The last time we talked was in Porvenir - a night and hundreds of miles away. I say we'll call back, but his is a welcome voice.

The VIPs arrive. I talk with Jon and say we have, as yet, no pictures out of here. Jon agrees that it has always been a less than 50-50 proposition but we'll keep trying everything we can. The main suspicion is that the dish line-of-site to the satellite is so close to the side of the mountain a mile away, the signal cannot punch through the heavy mist and snow pushing off the mountain face by the prevailing wind. We had suspected this in map readings in London, but it had appeared to be achievable.

In easier situations, one can measure these things for uplink power - what does that matter now if none of the signal is getting out? I call London again via the Inmarsat satphone, which is thankfully working, and explain the problems here. Madrid is receiving our 'signal carrier' but no signal on top. London understands and will wait for whatever we can give them. They wish us luck and sign off.

I ask Roberto to take a photo of me pointing at the sign for the end of the Pan-American Highway. I return the favour and send him the photo by letter from London weeks later.

Readjust audio settings

The IFB talkback kit needs adjusting so I call SMCR again in London on the briefcase satphone. I power up the mixer and radio transmitter, and ask London to read something to me. An input gain somewhere is too low. I had wondered if there were other system gain controls behind some of the console volume knobs I hadn't uncovered when testing it in London.

They read aloud and I find the culprit and adjust the low audio we encountered at the last Tx with the VIP earpieces. It wasn't a show stopper, just not quite at the right level. That fixed, a quick look at the mountain and the dish and I can't help feeling a wave of disappointment and exhaustion... so far! so close! I walk away now with nothing to do, past the end marker to the highway. There seems to be a slatted walkway heading nowhere, so I just keep walking, heading nowhere, drained of energy, thinking it would all end just like that, with nothing more to transmit.

Walkway to paradise - Lapataia Bay

I walk through the trees and what I find there just blows me away. There’s a land's point jutting out onto a lake, frozen in places. It's unbelievably beautiful and silent out there, an amazing tranquility. It seems to give me a deep feeling of peace, a truly magical experience. It's silent but for snow sounds in a light wind. Further away to the left, the mountain blocking our path has much more violent winds blowing off its face.

When I return it doesn't matter anymore - who cares? we tried and it didn't work, so... at the end of the day we pack up and go home, that's what happens. I smile to myself. It'll be ok but less than what I hope for. I'm never satisfied with that. Keep trying! what's the use in giving up?

A quick check with Billy - he's on the phone to Madrid - no joy, but whatever we're sending is now linked all the way through Madrid to SMCR in London and on to Mission Control at London Studio. If anything happens it'll go all the way through.

Jon and the VIPs are very up and happy and joke with the crew and carry on. The clouds are beginning to lift.

Signal received in London!

Twenty minutes later, walking back to the satellite truck, we glance up at the mountain - clear sky! Unbelievably, just like that, Billy yells out that Madrid has our signal. That means London will have it too.

I whoop and high-five Billy. Yes! Patricio grabs me from behind in a neck-brace and punches Hernan in the stomach, who mock doubles over. I remember that clearly - everyone was laughing. Roberto beams away in sheer joy. Jon comes running over. We've got it Jon! we can go live in five minutes! Mission Control first needs to be called to set up the IFB talkback - time is what we don't have now.

Satellite broadcast from South America – live from Lapataia Bay

Nic helps me out and wires up the VIP earpieces. I open up each earpiece on the audio console to the programme coming in from London, (the crew already had it on) and hear the studio calls to standby for the cross, as the programme goes out live in Europe. The announcer says they will shortly be going live to South America - Jon has a headset also and hears it too; he looks at me and smiles with a nod. Suddenly, we're live. A question comes through, then another, and the programme runs itself - I'm oblivious to the content. Without sleep, this is still an exquisite feeling, and I find myself pacing back and forth behind the mixing panel, out of camera shot, feeling great.

Onwards to Ensenada Bay – the last transmission

Patricio, Roberto, and Hernan have already left for the last Tx site, to set up the portable generator and other equipment.

We finish the Tx. Now the camera crew and I have 20 minutes to pack up the kit and take it 7 miles (12 kms) to the last Tx site - Bahia Ensenada Bay, the place of much disputed location in London meetings. It’s a rugged journey in the wilds, and we're running late for our transmission slot.

The camera crew head off in a jeep from the park ranger service, and another waits for me. The ranger drives me from Bahia Lapataia to Bahia Ensenada. I'm completely somewhere else, in a dream, light-headed from lack of sleep, and happy for some strange reason. The scenery is breathtaking, the morning weather has lifted and turned the mountains pristine white in the sun against a deep blue sky, flecked with clouds. When we get there, I apologise for not talking, and he smiles and says he understands.

Bounce the signal by microwave back to the main dish

Unbelievably, Billy and his team of engineers have worked magic. We were never going to get live out of Ensenada Bay - too many mountains, wrong line-of-site to the satellite. Billy has a small .4m microwave dish - in fact, he has four of them. His engineers locate one dish near the camera location on the beach at Ensenada Bay, and they have an inflatable dinghy to take two to Isla de Tierra del Fuego, out in the bay.

The fourth will be close to the main uplink at Lapataia. He's going to bounce the signal through the small dishes to get to the big one there. Brilliant. They must be line of sight, one to the other. With 14 hours sleep in close to 90 hours, I can still smile.

The last transmission

And so, to the last Tx. The generator needs to be moved behind the concrete pier - too noisy. Santiago and I lug it to its new position.

Patricio is dead on his feet, Hernan can't think, setting up the small microwave dishes with the other Keytech engineers. Nic runs out audio and video cable for us - 50m. I cannot locate the Pacific Ocean Region - East (POR-E) Inmarsat satellite - it should be in a northerly direction towards the Equator, allowing for where it is located on the equatorial line around the world, in its geo-stationery slot, and roughly over the east side of the Pacific Ocean. I punch in and change to another satellite - Atlantic Ocean Region East - AOR-E. Still no joy. Unbelievably, I locate one of them perfectly due South - I cannot explain and have no time. David – our London engineer - tells me in London later that the area suffers from extreme magnetic deviation, but due South?... impossible. We are only 60 miles from Cape Horn.

(It was interesting for me to learn later, from reading the Genoese pilot’s 1520 account of Magellan’s voyage through the Strait that now bears his name, that “as soon as they went out from the straits to the sea, they made their course, for the most part, to west-north-west, when they found that their needles varied to the north-west almost two-fourths”) [6].

According to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, (NOAA), the variation (called the declination) for 1994 in Tierra del Fuego was 14 degrees east of north; in 1590 (the earliest record shown online), it was 20 degrees east of north [14], so the extreme magnetic deviation I experienced remains a mystery.

Rewire audio

London has pictures but no audio again. We check and re-check, and, in our tiredness, discover that we wired the audio wrongly. We find the audio connected into the betaSP recorder, not the microwave, and quickly replug. London has audio. Natalie Goodall stands waiting to camera, ready to broadcast. The London studio presenter is flustered by the delays; they interrupt an interview in London and cross live to us.

An Argentinian Coast Guard ship steams into view and almost spoils the picture, threatening to cross the microwave link to the Island. Suddenly there's a cloud of smoke, all stop, and the ship backs up – they must have acquired the microwave signal we're bouncing off the island to the uplink.

We're live.

Natalie is asked - how was the trip? She never went on the trip! she lives locally and is there to be asked about conservation. London covers by saying there's a problem with communications. There's no problem! - she can hear perfectly! but she is thrown by the delay, and hearing a second studio question come through her earpiece while trying to answer the first question.

Monica Kristensen is brought on in Ensenada to bolster the live piece, but Natalie has quickly worked out the need for timing one’s response after hearing the question fully, and then speaking strongly and continuing to answer, regardless of London breaking in and talking over her. She responds very well with an important piece to camera about local conservation.

It all goes out live with an awesome view behind, but I feel simply drained. There's still four hours of packing up before we get back to the Hotel.

A successful event

The story really ends on that beach.

We had champagne and took photos of each other as though we were conquering heroes - it was great fun.

There, a little later, on the pier in an overwrought state, I thought well stuff it! I can explain the cost to my boss in London later. I picked up the Iridium satphone and called my girlfriend (now my married partner) in London. The scenery was breathtaking.

Sleep did not come in great lengths over the next few days. It's a complex process which took more than two weeks - it happened like this also at the last big event I was involved in, the '91 G7 Economic Summit in London. I spent some time with the crew, walking around Ushuaia, having a few beers, and soaking up the magic. Two days later, at the airport, I said goodbye to Roberto, Patricio, and Hernan with a phrase I wrote down for them - 'Long may our paths cross, your friend, Brent'. What a team! What a job!

Roberto would drive the van back to Río Gallegos, and Patricio and Hernan would pick up the dish in Río Gallegos, and continue to Buenos Aires over the next week – over 1,900 miles (3,000 kms) away.

The scenery was simply beautiful as they left us at the airport.

The magic of South America

Ushuaia is a magical place – there's something about it I cannot explain. The people, the scenery, the sense of a deep connection to nature, and the southernmost city in the world. Part of myself has been captured by Patagonia ever since.

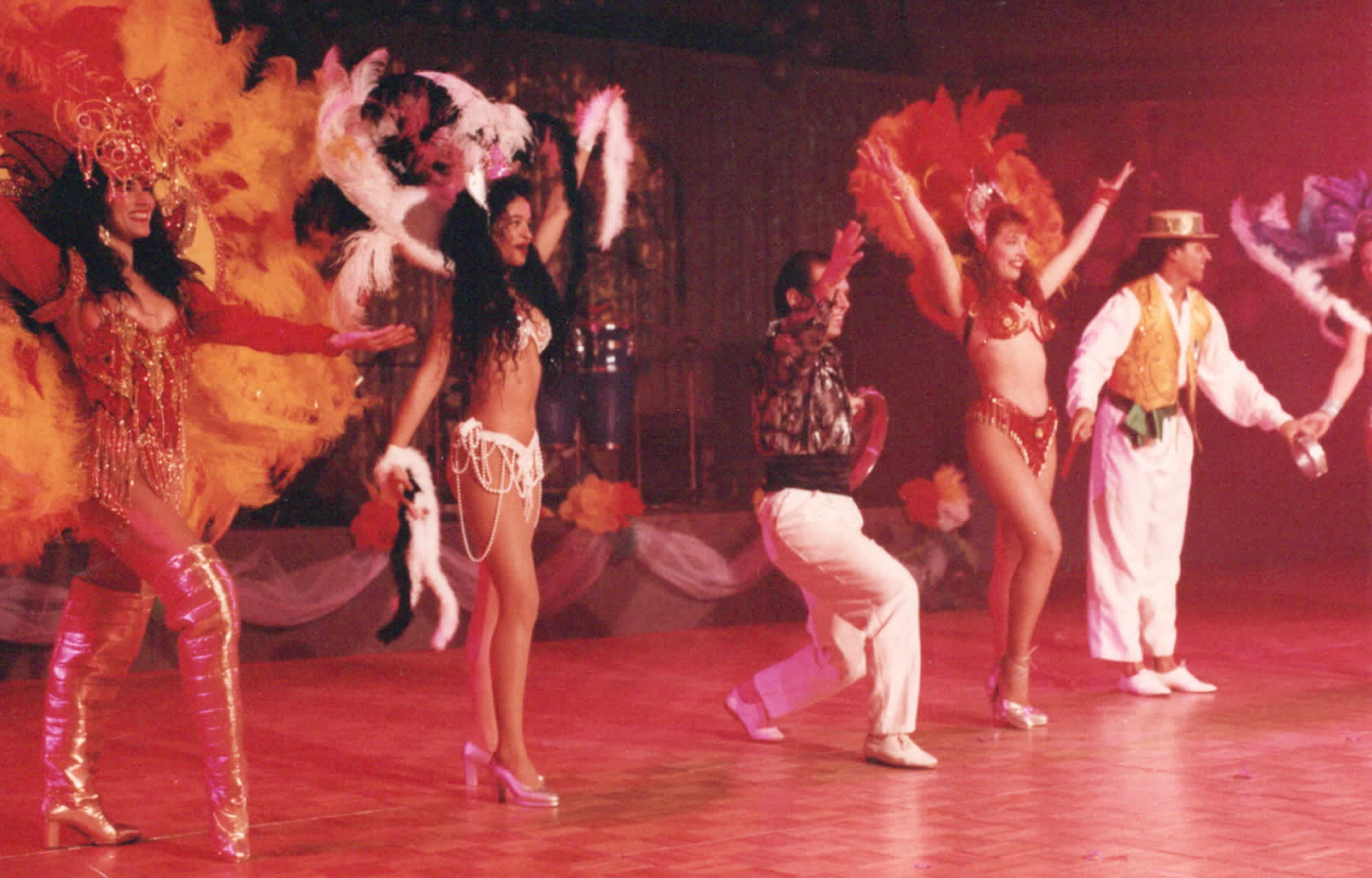

The VIPs and production crew arrived at the airport and we all flew back to Buenos Aires. That afternoon I went wandering and found a street performance - real tango – amazing.

That night was our last in South America; we all went out to a show, which was wonderful.

We flew out to London on Sunday night. All in all, a great experience, great teamwork, the VIPs, everyone was fantastic, and an excellent crew.

Room 5000 - a short story I wrote in 1981 about a computer becoming sentient

Newsletters

TFS#09 - What do Neoliberalism, Friederich Hayek, markets, algorithms, AI, and creativity have in common? We delve into these subjects for more connections

TFS#08 - What are the correlations between growth, debt, inflation, and interest rates? In this business edition of The Fragile Sea, we go hunting in corporate, institutional, and academic papers for insights in the face of heightened political, economic, corporate, and environmental risks, and more besides!

TFS#07 - We discuss a mixing pot of subjects - the state of AI, will there be food shortages this summer? good things and not so in energy, pandemics - are we ready? some remarkable discoveries, and more!

TFS#06 - Can AI produce true creativity? We discuss music, art and creativity, why human creators have a strong future, and why we must assure that they do

TFS#05 - Practical guides for implementing AI, in other news, a revisit on CRISPR, and events in spaceweather, fake publishing, spring blossoms, and more!

TFS#04 - Has Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) arrived already? We look at the goings on in AI over the past four months

TFS#03 - AGI and machine sentience, copyright, developments in biotech, space weather, and much more

TFS#02 - Sam Altman's $7trn request for investment in AI, economic outlooks, and happenings in biotech, robotics, psychology, and philosophy.

TFS#01 - Economic outlooks, and happenings in AI, social media, biotech, robotics, psychology, and philosophy.

AI Connections Series

[1]: Wikipedia, 'Río de la Plata' Wikipedia, 2024: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=R%C3%ADo_de_la_Plata&oldid=1184606696

[2]: Wikipedia, 'Patagonia', Wikipedia, 2024: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Patagonia&oldid=1182852523

[3]: J. Isabella, 'The Yaghan Rise Again', SAPIENS, Apr 2022: https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/the-yaghan-rise-again/

[4]: Wikipedia, 'Yahgan people', Wikipedia, 2024: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Yahgan_people&oldid=1187344122

[5]: Wikipedia, 'Ferdinand Magellan', Wikipedia, 2024: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ferdinand_Magellan&oldid=1184472025

[6]: P. Halsall, 'Ferdinand Magellan’s Voyage Round the World, 1519-1522 CE', Jun 1998: https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1519magellan.asp

[7]: M. Simon, 'Fantastically Wrong: Magellan’s Strange Encounter With the 10-Foot Giants of Patagonia', Wired, 2014: https://www.wired.com/2014/09/fantastically-wrong-giants-of-patagonia/

[8]: C. Williams, 'Scots shipwreck inaugurated as Argentinian Falklands War memorial', The Herald, Mar 2023: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/23356697.falklands-war-scots-shipwreck-inaugurated-argentinian-memorial/

[9]: Patbrit, 'British Club, Río Gallegos', 2014: https://patbrit.org/eng/clubs/rgclub.htm

[10]: C. C. Callahan, 'Butch Cassidy - Fiction and Facts', (date not shown) http://www.thelongridersguild.com/stories/callahan-cassidy.htm

[11]: iMariners, 'Everything You Need to Know About the Strait of Magellan', April 2023. https://imariners.com/strait-of-magellan/

[12]: S. Mambra, '5 Strait of Magellan Facts You Must Know', Feb, 2021: https://www.marineinsight.com/know-more/5-strait-of-magellan-facts-you-must-know/

[13]: Globalcom, 'History of the Handheld Satellite Phone', Globalcom Satellite Phones, 2019: https://globalcomsatphone.com/history-of-the-handheld/

[14]: NOAA, 'Historical Magnetic Declination Viewer', (date not shown) https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/maps/historical-declination/

Comments ()